My random or stray thoughts on literature or theater are not worth much. So I am contemplating a suspension of blog activity.

The long essay that I have had designs on appears not about to come to pass; in the meantime I feel aware of the larger trajectory of my "illustrious (writing) career" (to quote Richard Huttel), and that the time to leave prose altogether is approaching. At least I would wish it so.

If I can, I will take some of my essays, along with material from my blog postings, and compile a book: the nearest I have come to literary criticism. Blog posts will have to be refashioned, more or less, but given how scattershot and non-essential most of them are, it will be hard to make a cohesive whole. For me it will give closure to the experience.

My short term goals are: to finish a play I began last May, by the end of May. And to assemble what I expect to be my final prose book. (The others are not available at this time, and I may not have the time or energy to render them publication-ready.)

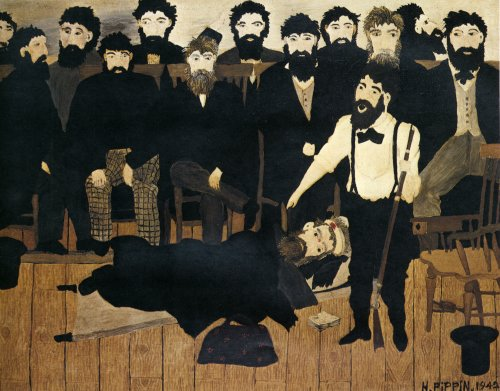

A longer-term goal, which may be unrealizable, will be to complete a larger dramatic project (or two) that I have in mind; and then to bid farewell to the stage much as the gentleman about whom I blogged a few days previous.

I foresee no poetry; all that I have done for a while now is incidental—commemorative of this or that occasion, public or private. This is by no means (necessarily) a "parting shot" or a saying of farewell—but thank you for reading.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed