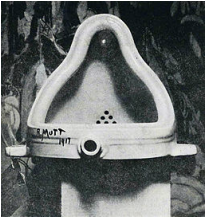

I've listened to the readings and conversations at Art International Radio from November 11, 2009; the talk on The Waste Land from July 23, 2012; and the interview for the Incognito Lounge from November 12, 1991. But certainly the most instructive—the program from which I learnt the most—was her lecture on Duchamp's "Fountain" from April 25, 2011. (I see now that some of these are available as videos, but I only had access to the audio files, which I would find preferable regardless.)

The program is a long talk on Duchamp, followed by about fifteen minutes of relating the body of the speech to literature, and then a fifteen minute Q&A. At the start—the first four minutes perhaps—are a sheer delight, as the voice of Al Filreis invites people to move their seats forward to let people who show up late, or in fact, on time, be able to sit in those places.

Duchamp is not pivotal in my cosmogony—so the main portion was not without its tedium, but I felt I had learned something at the end, and let me try to briefly put into words what that was. (There are applications to "Conceptual writing," that Duchamp-derived literary genre of which I only learnt the existence two months ago.)

While it has been argued about for a century (and this is not Perloff's point, but my own conclusion drawn), what Duchamp essentially did in making his objet d'art "The Fountain," was to make a copy—almost an exact copy—of Michelangelo's statue of David.

The David had been copied before; indeed, one of my treasured memories from a period of youthful employment at one of Chicago's grand department stores (now out of business, or rather transmuted into something quite different under a different name and different ownership), was coming off of the elevator and seeing a hideous copy of the David's face. The expression was grotesque—no matter how adept the physiognomy of form, body and musculature, it is always the face which sabotages copyists of Michelangelo's masterpiece.

Duchamp was protesting exactly this kind of copy; where art replicates itself upon itself. He considered that he was doing something different; to what extent he realized his profound invention cannot be known. He duplicated the David point for point.

Once you realize that, it becomes obvious that the experiment might as well be said to have run its course; rather than making copies, it is time for artists to do something original.

Clearly, a performer such as Goldsmith, when he reads the traffic reports, or a narrative of the Kennedy assassination, or an autopsy, believes he is making an imitation of some great work of art (in the line of Duchamp) —Homer perhaps. And that is exactly what he is doing.

Mechanical reproduction can only go so far, however (or take one so far, I might say). Conceptualism as a genre may not have been "killed" (to repeat the kind of hubris one finds online), but it certainly would seem to have depleted itself, though it might well go on regurgitating copies ad infinitum.

Keats, of course, did not imitate Shakespeare; or, if he began in imitation—what novice does not?—he at last became something greater and more profound: Keats.

In the sense, as per Perloff, that Duchamp created art by making a "choice," then that explains the cries of "colonial aesthetics" in application. How else might one refer to it? (Art—and, to varying degrees, artists—have always been owned by the wealthy. That is not the question.)

Where the denouncers of Conceptualism trip themselves up, simply, is that though they decry copyists and imitators, yet they have not figured out how to do what Keats did: be themselves. Until they achieve that, denunciations remain impotent, fruitless, and not even fallow.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed