At Court Theater in Chicago

We had—in name—Chicago Shakespeare Repertory under Barbara Gaines but they performed nothing in repertory. It may have sounded nice, but I believe the company never had any intention of living up to its name—which, wisely, in later years was changed to Chicago Shakespeare Theater with the "Repertory" dropped. (It has lived up to "Chicago" better than it has "Shakespeare"—but at least Gaines has shepherded it into a well-funded high profile venue with one of the best physical plants in the city.)

Newell not only talked the talk, he walked the walk—or at least attempted to. His first season's offerings included something by Molière run concurrently with something by Tom Stoppard, with the same cast in both shows. I did not see either, which I now regret, because the experiment was soon abandoned in favor of the usual multi-show preset season as is prevalent in American theater. (That the annual pass is its artistic bane is something I have written about elsewhere.) Rather than paint Newell as a "short hitter," I presume he caved in on his ambition for sound financial reasons. Contemporary theater may simply not support the repertory concept (though Jeff Watkins has argued cogently in favor of Shakespeare's model here).

Newell's directorial efforts have largely been disappointments to me, also—though not the disaster of a Gaines production—but so has his selection of plays.

(Here, in the interests of "full disclosure," I must let my personal "sour grapes" enter into the picture: at particularly the time that Court seemed to be running a Stoppard play every season, they sent me a curt rejection letter advising that Court only mounted "classic" plays, and would not consider glancing at one of mine. Keeping an eye on their season since, I've had ample occasion to feed my disgruntlement.)

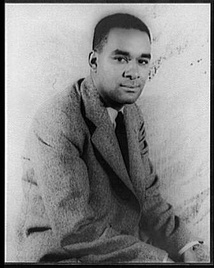

When I heard that Court was planning to do an updated version of Richard Wright's Native Son, I expected the worst. Actually, I originally heard that it was to be an update of Paul Green's theatrical version which was staged by Orson Welles and John Houseman in 1941—possibly with some prestigious hands involved in the the modernization. What I heard was wrong; but even so, when I learned it was going to be an entirely new play, my trepidation heightened. Adaptions are done routinely—of this novel or that—and inevitably produce mediocre results. Usually it feels that a theater company longs for the advantage of an already recognizable name—but the best books, by their nature, will not easily translate to the stage and so inferior theatrics make the rule not the exception. (Here also, I have been accused, rightly, of sour grapes.)

Court's production of Native Son, in conjunction with American Blues Theatre, recently opened. I attended, and was pleased that my low expectations had been exceeded. First off, let me confess, I had seen a snippet of a review by Chris Jones in which he announced that the script was "difficult... to stage."

“You dunderhead,” is how my thoughts (nursed on the decades of sour grapes) more or less ran: “How can you declare that about a brand new script? Obviously it’s a faulty play!” This kind of spur-of-the-moment, hot-headed judgement, based on too little (or prejudiced) information, is all too common with me—and in this case I was wrong.

The play runs 90 minutes sans intermission, and is rather daring in technique: scenes bleed into other scenes in a jumble of non-sequential timeframes—often within a single sentence or that sentence playing a role concurrently in two very distinct scenes—and manages to keep the action flowing without getting jumbled up. The storyline remains coherent, even if one hasn’t read the novel (or so I presume, since I have).

The playwright is Nambi E. Kelley; and while, assuredly, there must have been challenges for director Seret Scott, from the audience one gets the sense of an experienced hand deftly in control—I hope, one day, I get the chance to read her published script, for reasons beyond ordinary curiosity.

She says, “[E]verybody has a relationship to the book”; for that reason, the “audience... has already made up its mind about what you are doing”. This perhaps demands clarification: The playbill states, “At the core of Native Son you have a Black male character written by a Black male, originally penned approximately 75 years ago.” Under the same racial paradigm, Kelley, also Black, would be closer in proximity to the novel than someone of another ethnicity (or nationality), so presumably intends “everybody” in a restrictive sense. Kelley describes her goal in adapting Native Son (which she was approached to do after having “not visited the book in years”) as “to dramatize thoughts and feelings that have so little room in our society to be expressed.”

Native Son was included in a survey class on Chicago literature I had with Paul Carroll. I remember vividly some of the conversations we had about the book, although, like Kelley, I too had not “visited” it in a long time—until I decided to undertake my own adaptation of it several years ago.

Not done by invitation but for reasons of personal satisfaction, my play is probably not stageable or publishable until some future date when the Wright novel slips into public domain status—though I consider it not technically an adaptation but a new work based on characters and themes of Wright’s creation. (It was the last of three “derivative” works or works based on “preexisting material” in copyright terms—three plays the first of which is Sixpence and the Moon—done in 2008.)

Kelley’s structural discordancies (if you will) are easily understandable from an adaptor’s perspective. The novel is flawed—so I opined to Paul Carroll—in that it first tells the story, then appends a court scene in which the entire thing is rehashed. Kelley averted this bifurcation by virtually ignoring the courtroom scene except for (mainly) the interposition of one speech; whereas I avoided bipartite structure by focusing entirely on the courtroom with the story told in flashback (my title is Trial of a Native Son). In either case, a straight, linear telling of the story would not have been possible dramatically. My running time would be longer—it being a two act—but I can't resist feeling that it would “be a hoot” to compare the two. I strove to locate any rights-controlling agency or estate, for permissions, without success—now that Kelley’s version exists I foresee no immediate purpose or likelihood for granting them. I studied the Paul Green iteration and it had aged poorly: time was ripe for a new version. Now there are at least two—and time will work on these.

Kelley’s condensation of the story kept the action moving at a fast clip. The iconic story functions better in the immediacy of drama than in the extended narrative of a formal novel. Wright’s genius lay in inventing the story, not the telling of it. Much miscast, he took the title role of Bigger Thomas in a film version which I have not seen.

Wikipedia writes of Wright's novel, "Wright was criticized for his works' concentration on violence. In the case of Native Son, people complained that he portrayed a black man in ways that seemed to confirm whites' worst fears." Paul Carroll and I discussed this. He felt that Wright's characterization was perhaps overdrawn: a protagonist with so few redeeming qualities would not engage the reader's sympathy. I felt the opposite—that Bigger Thomas functioned much in the same way as Shylock in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice—though at such a distance, alas, the reasoning behind my theory escapes me.

In his review at the Wall Street Journal, Terry Teachout admires the concision of Kelley's script, achieved

in part by eliminating Max, the white lawyer who defends Bigger. This works, too, though in the process she makes the major mistake of cutting the most important part of Bigger's climactic confession to Max: "I didn't want to kill! But what I killed for, I am!...I didn't know I was really alive in this world until I felt things hard enough to kill for 'em." I can't imagine that Wright would have permitted the sanitizing omission of so crucial an utterance, one that has not yet lost its power to shock.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed